Over the last six months, it’s been fascinating to watch Eric Adams, who has decent odds of becoming New York City’s 110th mayor, characterized as the most conservative candidate in the Democratic primary when it comes to policing. The former NYPD captain has been portrayed, in various forums as having outdated, regressive and pro-police views that would ultimately stymie racial progress and equality in the five boroughs.

First, let me say that there are numerous issues and valid criticisms to raise about Adams— a deeply idiosyncratic individual with a penchant for saying and doing odd things and, depending who’s doing the listening, making divisive or inflammatory statements.1 I certainly do not know whether or not he’ll be a good mayor, should he actually win the race. We will set that subject aside for another day.

But it is interesting to see him shorthanded, by opponents and in some media, as something like an enemy of police reform, because for many of the past 30 years, he’s actually been, in word and deed, the exact opposite— a staunch and constant police reform advocate, and an occasionally incendiary public commentator on the workings of the city’s police department. His views on policing and what’s wrong with it actually haven’t changed that much, over the course of three decades. In some cases his police reform positions were considered totally beyond the mainstream at the time when he first staked them out.

What has changed in the last 30 years are some New Yorkers’ attitudes about the NYPD. Some among the Democratic electorate in New York City have not only come around to where Eric Adams has been this whole time, when it comes to fixing the police, they’ve actually vaulted past him, toward a stance on police reform that’s so progressive it’s post-police.

With more than 100,000 additional absentee ballots yet to be counted, and rank choice votes yet to be tallied, there’s a possibility Adams could be overtaken in coming weeks by Kathryn Garcia or Maya Wiley.

But for a significant number of Democrats, particularly in a lot of Black and Brown neighborhoods, Eric Adams’s platform and his experience was the most appealing. His decades-long-career as a police officer was nowhere near the liability some commentators predicted it would be, and in retrospect it’s hard to understand how it could have been anything other than a net positive for him among New Yorkers who want cops who can help keep the city safe without being abusive or racially discriminatory.

That shouldn’t be such an insane thing to ask, yet it’s eluded every mayoralty for the whole of the city’s history. But it’s not only exactly what Eric Adams is promising he’d do if elected mayor, it’s what he’s been working toward for a very long time.

The early ‘90s

In 1991, Eric Adams was a transit cop and member of Black police organization the Grand Council of Guardians. The year before, 1990, the city had experienced a record-breaking 2,245 homicides, a number that diminished slightly in the two years following, but which was still, by today’s standards, astonishingly high. The city had its first Black mayor in David Dinkins, and a Black police commissioner, in Lee Brown, but racial tension and crime were extraordinarily high.

This was the year Adams, age 31, started showing up in the newspapers, advocating on behalf of transit cops.

By 1992, Adams’s name begins appearing regularly in the newspapers, the running book of New York City history.

Adams appears, again and again, with heartbreaking regularity, to comment or provide context when bad cops misbehave or brutalize or kill people, often Black people.

For many years, he was the firebrand, the cop the reporters called when they needed a reaction from a police officer unafraid to criticize the police department he worked for. Eric Adams “played the race card,” calling things and people and institutions “racist” at a time when it was more politically fashionable to proclaim that you’d evolved so much beyond America’s racist past that you’d become colorblind.

Adams apparently always saw color. At this point in history, it seems clear that much of the time his frame was correct. His frank assessment that race, and anxiety about race, were the bundle of nerves that wound and still wind through every piece of the city, and that talking candidly about it might be the only way to make things better, is a major through line of much of his career as a police officer.

1992

The first time I learned about the off-duty police officers’ riot that future mayor Rudy Giuliani helped lead at City Hall in 1992 was 24 years after it happened, in 2016, when political commentators were retracing the arc of Giuliani’s career to find threads that could help explain why he was doing things like calling the Black Lives Matter movement “inherently racist” and supporting Donald Trump’s presidential run.

Many of you are probably familiar with the event, or you may have already seen video footage of the riot, or read the coverage. But what happened was this: In September 1992, thousands of drunk, off-duty cops showed up at City Hall, led by Rudy Giuliani, nominally to protest Mayor David Dinkins’ proposal to transform the city’s police oversight agency, the Civilian Complaint Review Board, into an all-civilian body.

The “protest” quickly devolved into a riot. I won’t print the word some of the cops allegedly called Mayor Dinkins, the city’s first Black mayor, and then-City Councilwoman Una Clarke. Photos and limited video footage from the riot are terrifying. Jimmy Breslin’s column captured the details, including the awful language he reported police using.

Eric Adams called the riot a scene “right out of the 1950’s: A drunk racist lynch mob storming City Hall and coming in here to get themselves a [n-word].”

He’s quoted in another article: “We have been saying for years that the Police Department is comprised of racist Long Islanders who come into the city by day and leave at night with their arrogant attitudes and believing they are above the law,” Adams said. “Well, finally, the entire city was able to see what we’ve been talking about.”

The fact that some police officers and Rudy Giuliani said and did racist things, that some police freely used the “n-word,” was self-evident to many Black New Yorkers, whether in 1992, or in 2016. For some white New Yorkers whose view of Giuliani had over time flattened into a simplistic, rosier portrait of “America’s Mayor,” the guy who helped clean up New York and lower crime rates, the reminder of his role in the 1992 riot may have hit harder.

1992-1999

Another thing to know about Eric Adams is that for all the crystal clear insight he offers, he also has a remarkable track record of sticking his foot in his mouth, making some groan-inducing, head-scratching comments and gaffes — sometimes in the form of wild conspiracy-mongering, sometimes as incendiary but totally un-strategic race-baiting, and sometimes just plain weirdness.2

For example, it probably didn’t help David Dinkins’s 1993 mayoral re-election campaign when Adams tried to force Dinkins to meet with representatives of the Nation of Islam, at a time Dinkins needed to shore up Jewish support.

And it certainly didn’t help Dinkins when, in the waning months of the 1993 mayoral race, Adams, a Dinkins surrogate, criticized fusion comptroller candidate Herman Badillo, arguing the fact Badillo had married a Jewish woman instead of a Hispanic woman showed he didn’t care enough about the Hispanic community.

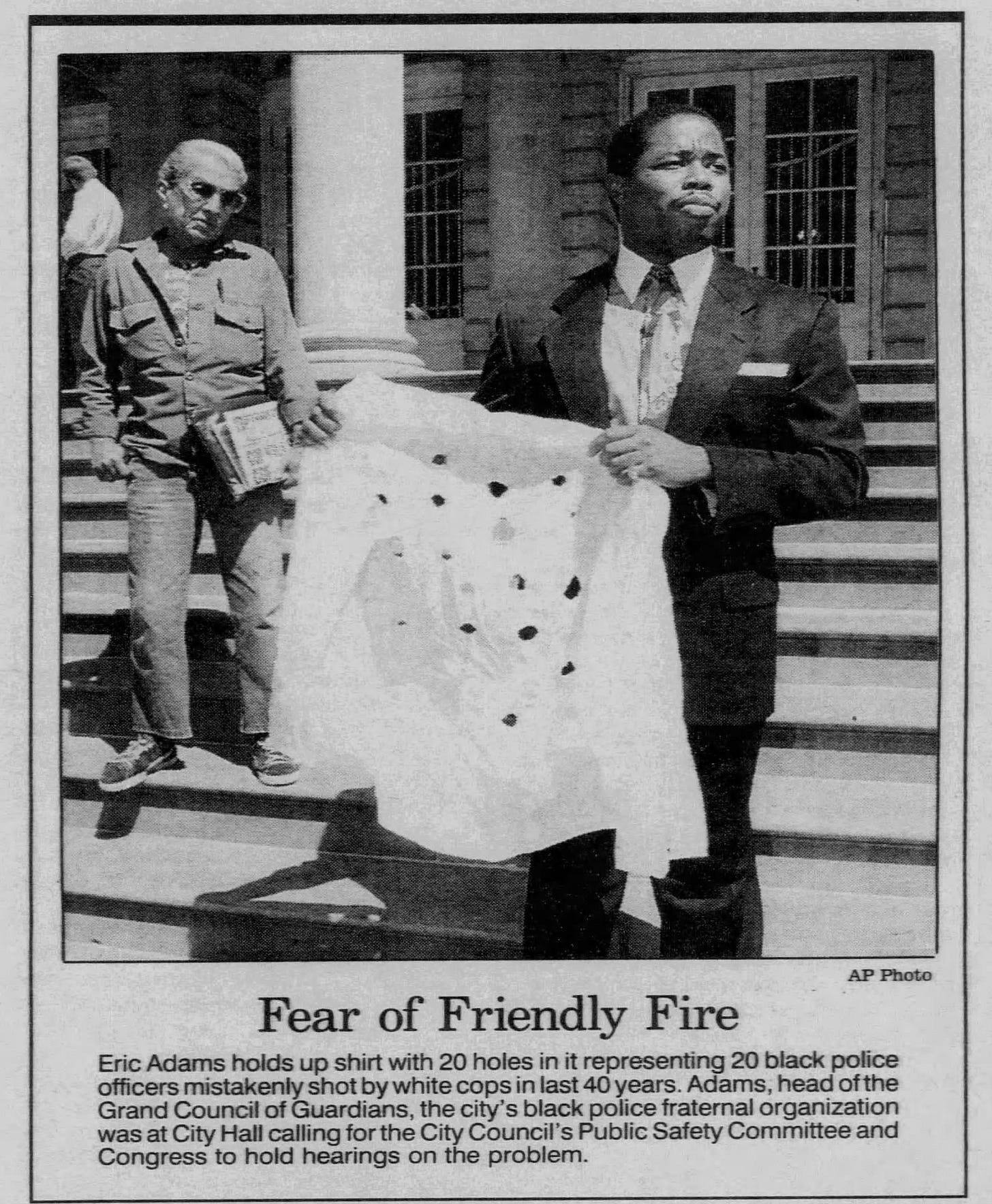

But after Dinkins lost to Giuliani, Adams kept agitating for changes at the NYPD, often a lonely voice calling for the specific and nuanced policy fixes he sought. He launched a campaign to raise awareness about “friendly fire” after multiple deaths and shootings of Black undercover or narcotics police officers by white officers. He advocated for partitions to protect the Black car and livery cab drivers. He called for restrictions on sales of toy guns after multiple kids were shot and killed by police who thought they were carrying real firearms.

Some of his contemporaneous criticisms of the Giuliani Administration are particularly poignant in hindsight, given how long it took for conventional wisdom to catch up to him. Almost two decades would pass before a federal judge ruled the city had used its stop, question and frisk policy in a racially discriminatory way. And many years went by before New York decriminalized some of the quality of life offenses that sent so many thousands of young people to jail, shattering some of their lives.

In 1995, after Giuliani’s first year in office, Adams was among critics raising questions about the possible excesses of Giuliani and then-police-commissioner Bill Bratton’s approach to crime fighting, which involved a massive escalation in arrests of children and teenagers. This article from Newsday, from 1995, lays out the numbers.

“By cracking down on quality-of-life offenses, you’re not really preventing the nonviolent youth from doing worse stuff down the line,” said Sgt. Eric Adams, chairman of the Grand Council of Guardians. “What you’re doing is stigmatizing someone who already feels he has two strikes against him because, most likely, he is poor and a member of a minority group.”

“Arrests of children and teenagers in New York City climbed nearly 30 percent in the first year of Rudolph Giuliani’s mayoralty, fueled by stepped-up police efforts to combat “quality of life” violations and, some argue, by deep cuts to city-funded recreation programs.”

I wasn’t here in 1995. I can’t pretend to know what it was like, how afraid of crime people were. Could the city have done something differently, to preserve public safety, without locking up so many young people? Eric Adams certainly thought so. A lot of other people seem to think so too, in retrospect.

Viewed through the prism of news clips about policing, the rest of Giuliani’s mayoralty, from 1995 until his departure in 2002, comes across like a terrifying catalog of provocations against the city’s Black and Brown residents, even as crime dropped dramatically.

In 1997, police officers tortured Abner Louima. In 1998, Black undercover officer Sean Carrington was shot by a white colleague. The same year, Rudy Giuliani explained away the fact Black police officers were disproportionate recipients of police discipline by saying Black cops used drugs more often. Giuliani, running for re-election, pointedly apologized that year to the family of Yankel Rosenbaum, victim in the 1991 Crown Heights riots, but refused to apologize to the family of Gavin Cato, the Black child whose death sparked the riots.

That summer, Giuliani refused a permit to organizers of a “Million Youth March.” When police shot 16-year-old Michael Jones in the pre-dawn hours one August day that summer, after mistaking the water gun he was carrying for a firearm, Giuliani blamed the victim — questioning not whether police could have acted differently, but why the young boy was outside and not at home in bed at the time he was shot.

In February 1999, four police officers fired 41 bullets at an unarmed immigrant named Amadou Diallo, killing him.

Over the next 13 months, police officers would shoot several additional unarmed Black men.

In a New York Times profile published in 1999, Adams sounded weary about the city’s refusal to deal honestly with the role that race plays in politics and policing.

“Lying is at the root of our training,” he told the paper.

“At the academy, recruits are told that they should not see black or brown people as different, but we all do,” Adams said. “We all know that the majority of people arrested for predatory crimes are African-American. We didn’t create that scenario, but we have to police in that scenario. So we need to be honest and talk about it.”

"The good people of this city were willing to give up civil rights for safety and prosperity. But we took a short cut. We were so fed up, we told the police agencies to do what you want. We are all to blame for Diallo." — Eric Adams, to the New York Times, 1999.

The city got the trial venue for the four officers who shot Diallo changed from the Bronx to Albany, where the officers faced a whiter jury pool. The four officers were acquitted in 2000.

"The courts have made a very clear decision that the taking of a life of an African-American because of the created fears of white officers is permissible in the state of New York," Adams said at the time.

"As long as four white police officers think a black man is guilty, that is enough to take his life. And that is a shame."

Here and now

In 2006, Adams retired from the NYPD and ran for and won a seat in the State Senate. It’s been 15 years since he was a cop. But a lot of his long-held ideas for fixing what ails the NYPD were views that got a re-airing during this election, because a lot of other candidates shared them. He’s been saying the city should appoint more people of color to high-ranking positions in the NYPD since at least 1992. He called for a city residency requirement for new recruits in those days, only to back away from the idea during this year’s mayoral campaign, even as most of his competitors embraced it. He’s been a proponent of community policing since the early ‘90s.

Adams has vocally opposed “defunding the police,” a position that aligns him with more moderate Black voters in the city, but also makes him a convenient vessel for white conservative voters who oppose most police reforms in general.

But his reluctance to disempower the NYPD as an institution is also arguably easier to understand when one considers he’d already spent a quarter century trying to fix the institution from the inside. He may be, finally, on the verge of actually being in charge, in perfect position to make the changes he has for so many years insisted are just what’s needed to mend what’s broken about the New York City Police Department.

There are areas of cognitive dissonance in his policy platform. It’s harder to square the man who once questioned Giuliani’s quality of life policing policy with the man who this year said the city should get tough on graffiti again, arguing “ignoring defacements and other quality-of-life violations only allows lawlessness to spread, and we can’t let that happen.”

He and a candidate like Maya Wiley, for example, advocated for very different solutions to the immediate problem of gun violence. But it is hard to find cause for cynicism about the underlying motivations in any of the mayoral candidates’ proposed solutions to gun violence. I do not presume to know which candidate is correct, if any of them are.

But I do think, after digesting several decades’ worth of news coverage from his public life in New York politics, that it’s very difficult to doubt Eric Adams’s earned credibility on the subject of police reform, or the sincerity of his desire for a safer city, for all of us.

Examples of said idiosyncrasy: The 60-year-old is a late in life convert to veganism, a change he says helped him stave off diabetes. He has an unselfconscious tendency to refer to himself in the third person. He slept many nights of the pandemic in his Brooklyn Borough President’s office. He once held a press conference where he displayed dead rats to reporters inside Brooklyn Borough Hall. He cut an insane PSA in 2011 showing parents how to look for drugs and other contraband hidden in their children’s bedrooms. At various times during the mayoral campaign, he’s said that his favorite movie about New York City was either“The Education of Sonny Carson,” the 1974 autobiographical film about a former teenage gang member and activist, but recently switched to“Taxi Driver,” the 1976 Robert de Niro film about a psychotic and violent cabbie. He named as his favorite concert one where Curtis Mayfield was paralyzed before he could even perform. His personal housing situation is too odd to neatly encapsulate here. In a lightning round of a mayoral debate, when each candidate was asked to name one thing they couldn’t live without, he cited“hot bubble baths…with warm roses inside.” I could go on.

There are probably too many of these instances to list here. There have been questions raised, often by Adams’s political opponents, about the credibility of some claims he’s made on the campaign trail over the years. In 1994, while challenging Brooklyn Congressman Major Owens, Adams claimed someone broke into his campaign office and stole the nominating petitions he needed to make it onto the ballot, and suggested the possibility Owens’s campaign was responsible. Another intense and bizarre story which Streetsblog actually investigated was Adams’s claim that he was shot at while driving in a car in the 1990s, possibly by another police officer trying to silence him. Adams also has a habit of deflecting even valid criticisms as racist.

Thank you for this excellent piece. I voted Garcia, but this helped me appreciate Adams and understand him better than any other profile I've read.

Sean Carrington was not shot by a fellow cop. He was killed while working undercover when the suspect shot him in the heart.